Broadloom Report: A decade of innovation in broadloom - Mar 2018

By Beth Miller

At its high point in the ’70s and ’80s, carpet was used throughout the home, and it dominated the commercial landscape. About a quarter century ago, it started steadily losing share. Today, on the residential side, it’s mostly used in bedrooms, and on the commercial side, it’s become a niche product, overshadowed by carpet tile and hard surface flooring. Carpet, however, has transformed over the intervening years-particularly in the last decade-driven by technological advancements in tufting, backings and face fiber.

A decade ago, broadloom was at the $10 billion mark and had just passed its revenue peak of $11 billion two years earlier, according to Market Insights. Today, the category stands at about $5.8 billion, a 42% drop in one decade. According to Chris Bryant, Shaw Industries’ VP of residential technical development, “As hard surface grows and carpet declines, we are challenged to make a better product. We’ve altered a lot of things along the way, but if you look at the finished product, it is easier to clean, better styled, worry free. There are a lot of things we’ve improved on versus products from the past.” In terms of design, he notes that there’s more variety and better visuals, adding, “We’ve got a lot of things that we did not have years ago. So from an overall design standpoint, carpet is better than it was years ago.”

“When you look at the last ten years with the growth of hard surface, [residential] flooring became more of a room-by-room purchase,” says Paul Comiskey, former president of The Dixie Group’s residential business. “When you look at room-by-room, I think the average price points went up, and people were really looking to make a statement in each room.” Today, broadloom has come a long way. In fact, it has perhaps reached a tipping point on the numerous options now available to consumers. Manufacturers are marketing pet-protection, waterproof, bleach-proof, delamination warranties, backing options, custom printing options, a multitude of construction options and seemingly endless possibilities for design.

A DECADE OF TUFTING EVOLUTION

The two primary contributors responsible for the tufting technology that is in use currently are both located in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Tuftco got its start as Southern Machine Company in 1960. And Card-Monroe Corporation (CMC), opened its doors in 1981. In tufting, CMC’s invention of the ColorPoint machine in 2008 kicked off a decade of change that has led to many of the major improvements and plethora of design options available in broadloom today.

CMC’s Infinity pattern attachment enables the production of multiple pile heights and a variety of textures and cut-loop effects with no limit to the size and scale of patterns that can be created. With the Infinity Attachment, the ColorPoint machine is capable of running at speeds over 2,000 rpm. Cut pile runs around 1,500 rpm, while LCL runs about 800. “ColorPoint technology makes it possible to place up to six colors or more anywhere in a carpet pattern with unmatched pinpoint accuracy, with no buried ends, to provide full-gauge coverage,” explains Robert Tamasy in his book, Tufting Legacies.

According to Jerry Hendricks, CMC’s technical sales representative, “Without the Infinity technology, ColorPoint would have been very difficult at best, if it even could’ve been developed.” Today there are three types of ColorPoint machines: Two-Color ColorPoint Cut & Loop, ColorPoint Loop and ColorPoint Cut & Loop, which can run up to six colors. It took several years for ColorPoint to take off, but a decade later, it has become the gold standard in tufting technology.

Currently, one of the innovations that makes ColorPoint so successful is that if it is running 1/10 gauge, it creates a denser product. “Before ColorPoint, if you had to add color into a piece of carpet, the surface was actually 1/5 gauge, but you had to bury an end of that,” says CMC’s Hendricks. “So from a performance standpoint, ColorPoint is always going to be much better than any other carpet we had prior to that.”

Another major milestone in the last decade was the development of high-speed level cut loop (LCL) technology, which essentially enables cut and loop to attain the same pile height by creating lower loops that, when cut, align precisely with the uncut loop pile. This opened the door for much more texturing and patterning, all on the same plane, and for the creation of very soft carpet that is essentially trackless, because the loop holds the cut pile in place.

Steve Frost, president of Tuftco, says, “Tufting machines today utilize servo motors that are moving extremely large amounts of ‘mass’ in terms of machine parts at speeds of 1,200 rpm, or 20 times per second. These movements place color laterally on tufting machines with shifting needle bars, as well as shifting backing systems, as carpet is being tufted longitudinally so that color is placed in the same way an inkjet printer produces a picture image.”

Recently, CMC shipped a tufting machine with the largest number of servos yet at 2,400-compare that to just three in 1989, when servo motors were first introduced. But, as Frost explains, the real innovation was in the computer system that controlled the servos. The Command Performance system by CMC is capable of altering a design, changing construction and calling back a previously used pattern-all with the touch of a button.

Tuftco’s management information system is called Tuft Worx. According to Frost, “We are able to more accurately obtain information regarding tufting machine performance and efficiency, as well as troubleshoot problems that are impeding better operation and efficiency. With our Windows-based operating systems, we are able to track and measure a whole host of metrics during the operation of tufting carpets or rugs that provide carpet mill managers with significant amounts of information on the productivity of the various styles they are producing.”

Locating ways to increase efficiency or save on labor costs all contribute to improvements in production. Bryant explains that Shaw is currently working to eliminate processing steps, like trying to twist and heatset yarn in the same step instead of having two different processes.

These days, many of the modifications to the tufting machines and technological advancements are done in-house at the carpet mill. According to Bryant, CMC is involved in some of these changes. CMC focuses a great deal of its tufting machine changes on feedback from manufacturers. Other improvements come about as a result of machine part failures, although CMC reports that it experiences less than three failures per million operating hours.

FIBER DEVELOPMENTS

Without advances in fiber technology, tufting would not be what it is today. The shift over the last decade from staple fiber to bulk continuous filament (BCF) fiber is arguably the single most important advancement in fiber technology. Bryant notes that Shaw doesn’t use spun yarns at all anymore-its fibers, both nylon and polyester, are all BCF.

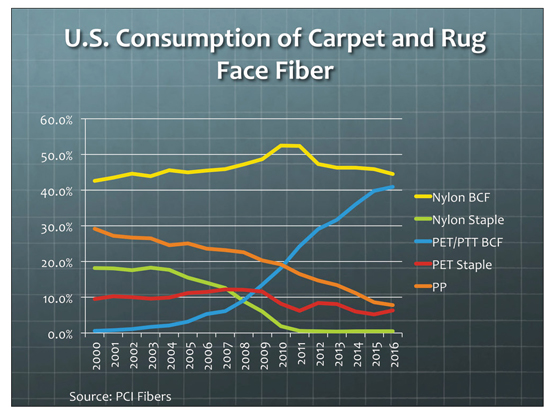

“Bulking technology has improved as extrusion equipment has advanced over the years,” says Rich Pattinson, president of Pharr Yarns. In 2007, nylon BCF accounted for 45% of U.S consumption in carpet and rugs. From 2009 to 2011, it rose approximately seven points, but then polyester face fiber hit the market, and by 2015 nylon BCF was back around 45%. PET BCF accounted for about 6% of the market in 2007 and has climbed steadily since then, now accounting for over 41%.

Another major development over the last ten years has been ultra-soft fibers, which James Lesslie, Engineered Floors’ EVP, calls the fastest growing development outside of shifts in face fiber polymers. PET has overtaken nylon in the push to provide consumers with a lower denier and softer feel. Currently, PET is 30% bigger than nylon residentially, says Lesslie.

There are several reasons for polyester’s rise to prominence. According to Pattinson, the polyester of today compared to the first generation is night and day. He adds, “You can put more weight into a polyester carpet to make up for what polyester can’t do in terms of its strength and robustness, but you’re still ahead because the resins are priced at a point where it’s about half the price of nylon.” In addition to the difference in the economics of resin, Pattinson notes that extrusion equipment has improved. “You can put more bulk in polyester in the extrusion process using technology developed by Oerlikon,” he says. “Today’s polyester fiber, because of advances in polymers related to the bottle resin industry and thanks to improvements in today’s extrusion equipment, allows for the development of properties that make for a better piece of carpet.”

IMPROVED BACKINGS

Broadloom adhesives and backing systems are also changing. Will Creswell, president of Tuftco Finishing Systems, says, “The same binders or adhesive coatings that were available when we entered this business for the most part remain the same today in their base polymer form [SB latex] or other types of latex compounds, PVC, polyurethane, various thermoplastics or hot melts.” More recently, alternatives to latex binders have been introduced. Urethane as a binder is gaining popularity for its added flexibility and resistance to cold, eliminating the need for acclimation. Engineered Floors has shifted some of its products to polyurethane as an alternative to latex in its new PureBac products. And Mohawk and Shaw have developed hot melt systems that use polyester and a modified polypropylene system, respectively, as binders. The alternatives provide a variety of benefits, including easier and faster installation with virtually no VOCs and no odor at all. Other features and benefits include moisture barriers and cushioning.

In addition to the binders in carpet backing, recent developments in coating equipment have allowed for the “application of lower weights of backing material per square yard, while maintaining the added benefits at enhanced performance levels,” according to Creswell, who points out that while these alternative polymers are costlier, it’s less material add-on per square yard than latex.

REACHING EQUILIBRIUM

While broadloom revenue has declined in the last ten years, it remains the single biggest flooring category in both units and dollars. However, consumers aren’t using carpet in the living areas of the home due to the seemingly endless hard surface options that offer moisture resistance, better durability, ease of maintenance-and the list goes on. But the improvements in carpet being produced today are making it a more viable competitor, including enhancements in stain resistance, pet resistance, moisture resistance, as well as its broad spectrum of design options. Today, consumers are looking for a reason to buy carpet explains Charles Monroe, CMC chief executive officer. “What’s going to compel them is beautiful carpet,” he says. “I think that has been a void in the residential sector. That’s what you see with these companies that are moving forward with ColorPoint and some other things.”

According to Zach Monroe, vice president of sales and marketing for CMC, since consumers are placing carpet in fewer spaces within their home, they are more willing to pay a higher price for carpet than they might have if they were carpeting the majority of their home. “With that higher price, they’re expecting more from a styling standpoint,” he adds. “The sales of patterned carpet in residential are much higher than they ever were before.” It’s worth noting that despite the higher prices, carpet on average remains cheaper per square foot than any other flooring category.

The hope is that consumers are learning the advantages and disadvantages of all surface types, where they are most applicable in a home and what suits their needs both financially and aesthetically. As for carpet’s decline, Engineered Floor’s Lesslie says, “The shipments of carpet, on a yardage basis, have been stable for five years. Residentially, carpet is fairly steady.”

What’s clear is that carpet, despite its loss in marketshare in recent years, will remain a category of consequence-and at a certain point it will stop losing share. In both the residential and commercial markets, there will always be demand for soft surface flooring. Shaw’s Bryant says, “I think things will come back in balance because there are certain advantages to hard surface and certain advantages to carpet.”

Tufting advancements made big waves in the 1950s. According to The Carpet and Rug Institute (CRI), “In 1950, only 10% of all carpet and rug products were tufted, and 90% were woven. However, in 1950, it was as if someone had opened a magic trunk. Out of that trunk came man-made fibers, new spinning techniques, new dye equipment, printing processes, tufting equipment, and backing for different end uses.” By the ’70s and ’80s, tufted carpet was gaining ground through even more innovation, such as the introduction of Hydrashift, a mechanism that “enabled the needlebar to shift, moving needles from one looper to another and making possible a wider variety of designs and patterns,” according to Robert Tamasy.

Despite the growth experienced in the early ’70s, many of the mills were forced to close or sell to larger mills. According to CRI, “The recession of the early 1980s claimed nearly half of the 285 mills that had been in operation in 1980; by 1992, the industry counted only about 100 mills, down dramatically from its early 1970s peak of more than 400.” The ones that did survive did so through vertical integration. Several mills invested in raw materials for spinning yarn, and some brought in finishing equipment and built their own dyeing facilities, while some of the larger mills invested in carpet manufacturing from start to finish. Currently, there are approximately 50 mills in the U.S.

Tuftco’s Steve Frost says, “The most significant changes in tufting that have occurred since my time of entering the carpet industry-46 years ago-have been the control of yarn in patterned tufting, and the speed at which that control is exercised.” Most, if not all, tufting equipment today is run almost entirely through computer control. Frost goes on to say, “Along with the development of computer systems to control machines has been the development of the primary elements those computers are controlling-that being servo motors of all sizes and types.”

Servo motors were applied to carpet tufting machines by CMC in 1989. This was a turning point in the industry, enabling machines to manufacture carpet much faster than they had previously, as well as produce designs that were not attainable prior to the innovation.

However, the biggest game changer in tufting technology came from CMC’s Infinity attachment-introduced in 2003-which gave the mills control of the individual ends of the yarn, creating the ability to produce an infinite number of patterns.

According to Tamasy, the concept of a secondary backing was introduced in the ’50s. Originally, cotton duck backing was used but it required the employment of an 18’ machine to manufacture 15’ carpet since the backing was expected to shrink by up to 20% during the finishing process. Cotton duck backing was finally replaced with jute, which was used from 1965 to 1975. Jute was problematic because over time it deteriorated. The backing materials used today consist primarily of polypropylene and urethane.

Cut pile was also introduced in 1953 in 3/16 gauge. Only one year prior, a 12’ wide machine was introduced that could produce loop pile in 5/32 gauge.

Related Topics:Mohawk Industries, Engineered Floors, LLC, Tuftco, Shaw Industries Group, Inc., Carpet and Rug Institute, The Dixie Group