Certifying Sustainability - August/September 2008

By Darius Helm

While the A&D community was arguably the driving force behind the greening of the built environment, now it’s starting to look more like the victim, as it finds itself buried in an avalanche of green information and misinformation, competing standards, and endless certifications. It seems as though everyone has his own yardstick, and who’s to say which one measures a yard?

Part of the problem is that it’s not easy being green. Sustainability is a relatively young science, and it’s complicated. At the same time, green products and programs are in high demand, so it’s a competitive advantage and it’s big money. That combination inevitably gives rise to a battle between perception and reality. What has a bigger impact on the bottom line, being green or appearing to be green?

In all fairness, the issue is not so cut and dried. The flooring industry, for instance, is populated with scores of sincere sustainability experts committed to seeing their businesses become as environmentally responsible as possible. However, there are just as many people out there who are more concerned about gaining the upper hand. At the same time, while many of the available standards are based on strict metrics, there’s also demand for standards with lower bars that to the untrained eye may look just as green.

Some of those standards are created through the efforts of industries with a stake in the outcome and without the consensus input of a broad range of stakeholders. This is fairly common, for instance, in forestry standards in Asia and South America, but it also takes place in the U.S.

However, not all standards with lower bars are designed to be deceptive. There are plenty of construction and product standards deliberately designed to encourage participation, to get builders and manufacturers on the road to sustainability without placing before them an unassailable barrier, and to permit the smaller players to compete with the giants or at least get through the door.

These standards and certifications generally have a few levels, like silver, gold and platinum, to reward a range of sustainability achievements, and the standards themselves are constantly reevaluated to be more comprehensive and to push applicants further up the mountain. Examples include the various LEED standards, the California Gold standard, GreenGuard, FloorScore and CRI’s Green Label Plus, NSF 140 and 332, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification, and certification programs through entities like Scientific Certification Systems, the Leonardo Academy, NSF International and McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry (see Designer Forum on page 20 for more on Bill McDonough and MDBC).

LIFECYCLE ASSESSMENT

All of this is little consolation to the A&D community and other specifiers, who still have to wade through towering stacks of documentation in order to make their projects green. The general consensus is that the ultimate in clarity is a comprehensive lifecycle assessment (LCA) standard that measures the social, economic and environmental impact of every element in a given system, like the manufacture of products.

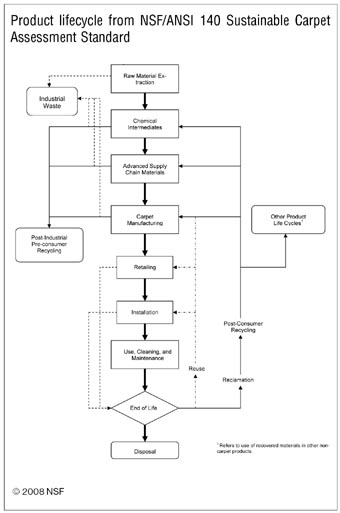

Such a standard would measure the impact of raw materials and chemical intermediates (many of which are sourced outside the U.S.), energy use, water use, transportation, installation, maintenance, the lifecycle of the product, and the final outcome after the product has served its useful life. To be comprehensive, such a standard would also measure the impact of the building and machinery through which the products are manufactured, the socio-economic impact on relevant regions, the environmental impact of merchandizing products with retailers, and so on.

Presumably, to be entirely comprehensive, the impact of having to go through the process of actually certifying all of these elements would also have to be calculated.

That’s not to say that there aren’t systems out there that can come close to hitting the mark. Many believe that NSF 140, the sustainable carpet assessment standard released late last year, is an excellent standard that covers all the key features, particularly when you get to the platinum level. A study of the 50 page document confirms that, as far as standards go, NSF 140 leaves few stones unturned.

The LCA based standard, developed through the ANSI consensus process with the input of a broad range of stakeholders, is based on quantifiable metrics for the achievement of sustainable attributes. NSF 140 is divided into five major sections: public health and environment; energy and energy efficiency; bio-based content, recycled content and environmentally preferable materials; manufacturing; and reclamation and end of life management.

NSF International, the developing body for the standard, is a not for profit, non governmental organization accredited by ANSI and OSHA, and it also provides third party certification. The organization is now working on the development of NSF 332, a lifecycle assessment standard for resilient flooring, covering vinyl flooring products, rubber, linoleum, and resilient flooring with PVC substitutes—Mannington Mills has already had its inlaid vinyl products certified to the draft standard.

Also certifying NSF 140 is Scientific Certification Systems (SCS), a third party organization that certifies a range of programs, including FloorScore, Environmentally Preferable Products (EPP), recycled and reclaimed content, and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certifications for wood flooring. Its NSF 140 certification is labeled SCS Sustainable Choice, and firms with carpet certified under that category include Bentley Prince Street, Flor and InterfaceFlor, Shaw, Mohawk, Tandus, Milliken and Mannington.

SCS is also developing what it considers to be an even more comprehensive LCA based standard, a lifecycle environmental declaration, in partnership with Leonardo Academy, an ANSI accredited independent standards development organization. The SCS 002 standard, on the verge of being released in draft form, is designed to use a common set of metrics to quantify all elements of an LCA. One of the big advantages of this standard, which is still two or three years away from its final form, is that it would allow, in the case of flooring, for LCA comparison across categories—for instance, between broadloom and vinyl flooring.

Such a standard would provide another step toward clarity and would greatly streamline the specification process, but it’s still a long way away.

A SOFTWARE INTERMEDIARY

A software tool has been developed by Georgia based Viridity Inc. that enables specifiers to find green products and evaluate their contribution to a range of ratings systems with just a few clicks of the mouse. EcoScorecard reviews a manufacturer’s products for sustainability criteria and plugs the information into its software, which calculates the various ways in which the products contribute to all the green ratings systems in North America.

Not only does EcoScorecard do the calculations for all the LEED systems, both commercial and residential, but it covers California’s CHPS, the Green Guide Health Care, LABS21 and the National Association of Home Builders’ Green Building Standard. The firm is also working on incorporating various international standards.

Firms signing on with EcoScorecard first pay an upfront fee for the comprehensive evaluation and incorporation into the software system, and also pay a monthly fee for the service, which includes constant updates as rating systems (like LEED 2009) are u

pgraded.

The end result is a specifier’s dream. All a designer has to do is go into the manufacturer’s website, click on EcoScorecard, choose the product or products and relevant ratings systems, and enter the quantity, the cost, and the zip code where it will be installed. A click of the mouse and the embedded algorithms produce product documentation, in a saved project folder or as a PDF, that spells out as clear as day the exact contribution the product makes—in a format ready for inclusion in the submission process.

The search can be conducted by product or by selecting various sustainability characteristics. Either way, it eliminates the need for specifiers to pick products one at a time, pore over all the specs, get out calculators, and go through the laborious process of figuring it all out for themselves. The process is also ideal for mill reps to better understand the sustainability contributions of their products and to illustrate them to clients.

It’s no surprise that EcoScorecard is gaining clients at an accelerating pace. At last year’s GreenBuild, two flooring clients had signed on: Armstrong and J&J Industries. Now Mohawk is offering the system for its commercial brands, and many of the biggest carpet companies are also evaluating the program. The more clients that sign on, the greater will be the utility for specifiers, who will be able to rely on the program for a broader range of their design needs.

EcoScorecard also has clients in the furniture and textile industries, and by this year’s GreenBuild anticipates that its software will be used by at least 30 brands. Currently, EcoScorecard serves the interior products and construction products industries, but it has already developed plumbing modules and is in discussions with window, roofing and siding manufacturers.

|

GREEN BUILDING UPDATE |

Copyright 2008 Floor Focus

Related Topics:Shaw Industries Group, Inc., Mohawk Industries, Mannington Mills, Armstrong Flooring, Carpet and Rug Institute, Greenbuild International Conference and Expo