Building a Green Foundation - August/September 06

By Darius Helm

Recycling carpet and keeping it out of landfills has been one of the primary objectives of the American carpet industry for the past ten years now. Yet for all the industry’s efforts and accomplishments in making its businesses more sustainable, finding effective ways to reclaim used carpet and get it back to a place where it can be processed has been its single biggest challenge. After all, if an industry that makes products from fossil fuels can’t reclaim those products and recycle them back into more product, it can’t claim to be green.

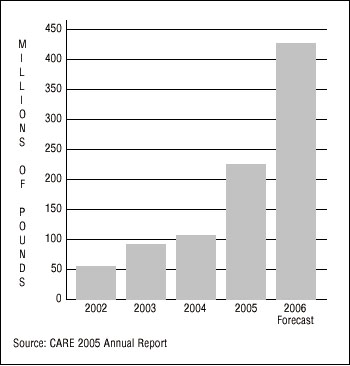

LANDFILL DIVERSION RATES

The good news for the carpet industry is that a reclamation infrastructure is in fact now being built, largely under the guidance of CARE, the Carpet America Recovery Effort. CARE was formed in 2002 by the Carpet and Rug Institute, in collaboration with the carpet industry, federal, state and local government agencies, even non-governmental agencies. The movement is supported by carpet and fiber companies, contract dealers, established recyclers, and a growing group of entrepreneurs who see opportunities for profit while improving the environment.

Interestingly, those opportunities have soared along with the soaring cost of energy. If oil were still $25 a barrel, the economic outlook for the reclamation business, and for green programs in general, might not be quite so rosy.

There are three distinct reclamation streams for carpet. One goes back into carpet, generally as padding, though the re-opening of Shaw’s Evergreen facility next year will turn a lot of reclaimed carpet fiber right back into new fiber. The second stream takes carpet and turns it into something else, such as railroad ties or automotive parts. The third stream uses carpet as fuel, with a BTU value by weight about the same as coal.

The first stream is the greenest because it recycles the material back into the carpet industry, enabling the industry to use less virgin material. The second stream is nearly as good, but the problem with carpet recycled into other products is that the process is then beyond the control of the carpet industry; the responsibility is shifted, and there’s no way to stop it from being downcycled and eventually ending up in landfills anyway.

The third stream is the least desirable scenario because the reclaimed material is lost forever. On the plus side, though, it’s burned for energy, which reduces the need for fossil fuels.

How Reclamation Works

Carpet reclamation is a complicated business; every job is unique. In a typical scenario, a client—perhaps a facility manager at a major corporation—will contact a mill with a request to have old carpet reclaimed. The mill gets the details and tries to figure out, based on the location of the job and the carpet specs, the best option. A key element is keeping things local, because long distance hauling of reclaimed carpet uses a lot of energy, which defeats the purpose.

Often the carpet goes to a sorter, who removes the backings and separates the different face fibers. The sorter will send it to a processor, who cleans the material and breaks it down so that it’s pure and usable. The processor then sends it to a manufacturer, who produces specific products like carpet backing or extruded plastic parts.

Many businesses cover all three processes. For instance, LA Fibers, the biggest carpet recycler in the world, sorts, processes and manufactures. So does Invista’s Calhoun Reclamation Center. Invista makes carpet backing, and what it can’t use, it ships to processors or manufacturers.

Further complicating the picture is the financial structure. First of all, the client usually has to pay something, at least to have the product hauled off for reclamation. The cost may be less than the landfill fee the client would otherwise face, or it may be more, depending on local landfill fees and the distance the carpet needs to be transported.

The waste hauler delivers the carpet to the sorter rather than to the landfill, and pays the sorter a fee to take the carpet off his hands.

Once in the hands of the sorter, the dynamic switches and the inherent value of the reclaimed carpet begins to assert itself: the farther downstream you go, as the product is processed, the greater its value.

2006: A Turning Point

The last year has been a pivotal one for the carpet reclamation business. For the first time, most of the material in reclaimed carpet has a market, and this has really changed the economics of the business for sorters, who can now resell all of their material, instead of reselling some and disposing of the rest.

What caused the change? Essentially, new demand. Just in the last four months, recycled nylon 6,6 is being used for thermoplastic molding applications; it had precious little value before that. Same case for nylon 6, which will soon have a new market: Shaw Industries’ Evergreen Nylon Recycling in Augusta, Georgia.

Evergreen was built in1999 to reduce nylon to caprolactam, its raw material, then make new nylon out of it with negligible loss. The facility was mothballed, though, about five years ago because the economics just weren’t working out. Shaw acquired 50% of it in last year’s purchase of Honeywell’s fiber business, then bought DSM Industries’ 50% share of the plant earlier this year. Today, with elevated oil prices that are unlikely to retreat much and a marketplace with a better understanding of the value of recycled materials, it looks like Evergreen’s time has come. The resurrected facility has been accumulating feedstock, and its presence in the market has attracted entrepreneurs eager to provide material.

Evergreen may have to collect close to 300 million pounds of carpet to get the 100 million pounds of nylon it needs for feedstock, since it basically has to act as a sorter as well as a processor. Other material it collects, like polypropylene and nylon 6,6, will be sent off to other processors.

The facility is on schedule to reopen in the first half of 2007. The initial goal is to process 30 million pounds of caprolactam annually, which will yield about the same volume of nylon fiber. Evergreen has a capacity of 100 million pounds, which the firm intends to hit a few years down the road. All of the nylon produced at Evergreen will go for Shaw’s internal consumption.

Further bolstering the market for reclaimed fiber is—surprise, surprise—demand from Asia, mainly from China and India. Demand from Europe has also grown.

CARE Approaches its Goals

Carpet accounts for 2% of U.S. landfill waste by volume and close to 1% by weight. At five billion pounds of waste a year, that makes it one of the biggest single contributors to landfills. CARE’s original Memorandum of Understanding in 2002, the year the group was formed, said its goal was to divert 40% of all that carpet from landfills by 2012.

How are they doing?

Last year, 225 million pounds were diverted, an increase of 108% over 2004. That represents 4.5% of the total poundage going to landfill, which is above projected S-Curve estimates, and CARE is more confident than ever that it will reach its 40% goal in 2012.

Of the 225 million pounds collected last year, 86% was recycled, mostly into non-carpet products, while 14% went to waste for energy or was burned in cement kilns, which leaves no ash. It’s likely that diversion for waste to energy will decrease over the next few years, as demand for recycled materials continues to increase. In fact, demand has already increased by 400 million pounds this year, according to CARE.

CARE developed two significant partnerships in the past year. One was with Tricycle, the firm which has been revolutionizing the carpet sampling business (see box on page 32), and the other is with StarNet, the independent contract dealer network.

Tricycle is contributing to the CARE effort with its nifty redesign of the organization’s website, www.carpetrecovery.org. New features include a user-friendly calculator that translates how much carpet you want to reclaim into how much will be saved in oil, BTUs, and the total weight diverted from landfill. The site also searches for carpet reclamation partners in any region. A little window toward the bottom of the home page tracks how much carpet has been diverted while you’re visiting the page—the running average is nearly four pounds a second.

Tricycle is also contributing a portion of the SIMs revenues it receives from CARE members to that organization.

CARE’s Alliance with StarNet

The StarNet partnership came out of a meeting in 2005 between Fred Wiliamson, StarNet’s director of special projects, and Bob Peoples, executive director of CARE, where they discussed the concern among StarNet members about shrinking landfills, rising dumping fees and consumer concerns about spiraling costs. Those concerns, coupled with StarNet’s code of ethics, which includes environmental sensitivity, led to the development of the StarNet CARE Reclamation Program and StarNet signing on as a corporate sponsor.

The program uses CARE’s network to help StarNet’s contract dealers find collectors, sorters and processors in their region, with an aim to build a solid network of local sites. StarNet members can now offer landfill diversion to their clients at costs that are more or less neutral to standard carpet disposal costs.

This partnership alone will have a visible impact on reclamation across the country—StarNet has 151 members with more than 240 locations and it’s still in a growth mode—and with both organizations working hard to promote the joint venture, it should also increase awareness.

StarNet has only been working with CARE for a year, but it managed to divert 10 million pounds of carpet in 2005, and it’s shooting for 50 million this year. The group gives its clients StarNet CARE Reclamation Certificates, which detail how much raw material, water and energy they’re saving.

Part of the goal is to expand the network of reclamation centers to cover all regions, since the more local the reclamation, the lower the cost.

Nationwide Reclamation Networks

CARE currently has about 15 reclamation partners scattered across the country. Members include Invista’s reclamation center in Calhoun, Georgia, Shaw’s Evergreen facility and LA Fibers, the biggest recycler of carpet in the world.

LA Fibers, which covers most of the West Coast, sorts product, processes plastics for the remelt trade, and makes 100% post consumer carpet cushion. Last year was the best year the firm has ever had, with volume up 100%, topping 100 million pounds of reclaimed carpet, nearly half of all carpet reclaimed in 2005.

Another business to watch is Boston’s Environmental Reclamation and Consolidation Services. ERCS is led by Paul Ashman, who has been involved for over a decade and is the only entrepreneur who’s been on CARE’s board since its formation.

ERCS was originally focused on education, information gathering and networking, but now that the full range of carpet components can be harvested and demand is driving the market, the firm is engaging entrepreneurs to build a network of regional sort centers to reclaim carpet anywhere in the U.S. Just in the last few months, five ERCS operations have been launched, with many more to follow. The firm’s website, www.carpetrecycling.com, provides updates on the growth of the network.

One of the newest partners is Columbia Recycling Corporation of Dalton, Georgia, which recycles carpet with latex backing.

CARE is also looking into expanding its efforts to other industries which generate similar waste, like ceiling tile and coving. No word yet on any new partnerships.

Residential Reclamation Challenges

As things stand now, carpet reclamation is limited almost exclusively to the commercial market, even though residential carpet volume is much greater. The problem on the residential side is demand. Nobody is really driven to reclaim residential carpet.

Reclaiming residential carpet has its pros and cons. On the positive side, it’s in high demand among recyclers because it doesn’t come with any nasty adhesives—it’s generally stretched and tacked to the edge of the floor. That’s a real plus for those in the business of processing carpet. Also, it has a heavier face fiber to backing ratio than commercial carpet, which gives it great appeal to those in the business of recycling nylon.

On the negative side, there’s not enough volume per job. Part of what makes the reclamation business profitable is collecting massive amounts of carpet. A single commercial reclamation can run over 100,000 square feet, while a home might yield 1,000 or less.

Residential carpet reclamation needs a comprehensive industrywide infrastructure to be viable. Local sorting centers and collection networks are needed to overcome the economies of scale. Installers and retailers are not in a position to stockpile vast quantities of reclaimed carpet, and there are no huge profits to entice them to invest the time and capital to make it work.

Big boxes like Home Depot and Lowe’s, though, are better positioned to serve as regional collection centers, and it’s possible that growing environmental awareness among their customers may compel the home improvement centers to reassign some of their warehouse space to carpet collection. Someday.

While there may be some environmental awareness in the residential market, it hasn’t impacted residential buying habits. Consumers don’t seem to care enough to generate change. But all that may change when the U.S. Green Building Council’s first residential protocols, LEED for Homes, are introduced next year (see the box below).

|

SETTING STANDARDS |

|

For the past four years, the CRI, initially with the Institute for Market Transformation to Sustainability, has been working on creating what it calls the Sustainable Carpet Assessment Standards. The goal is to make it easier for the A&D community to assess the sustainability of the carpets they specify, and to increase demand for green carpets. |

|

VANISHING ACTS |

|

Another green approach to waste reduction is a practice called dematerialization, which despite how it sounds does not involve twitching your nose and making stuff vanish. But the truth is, in fact, not so different. |

|

COMING SOON: LEED FOR HOMES |

|

Compared to the commercial market, there's next to no demand for environmentally sustainable construction or green products in the residential market. In an effort to generate demand and create an economically sustainable value added market in that segment, the USGBC has begun its latest set of protocols, LEED for Homes. |

For more about Green Players, see the August/September 06 issue of Floor Focus.

Copyright 2006 Floor Focus Inc

Related Topics:Shaw Industries Group, Inc., Starnet, Interface, Carpet and Rug Institute