Carpet Fiber Update: Developments in synthetics - Mar 2014

By Darius Helm

Though the carpet face fiber market is in the midst of significant transformations, and volatility from raw material costs has kept the market far from stable, 2013 was by most accounts a fairly quiet year. There was little on the way of raw material price increases, with reduced demand creating a slackness in the market that has dissipated the influence of many of those cost drivers, like refining capacities and demand from emerging markets.

In the U.S., though the residential market made some gains, it was more or less a flat year for the commercial market. And so far, this year looks like more of the same.

TREND UPDATE

Transformative fiber trends have continued to run their course. One that’s just about wound down is the shift from staple to filament. At the turn of the century, 30% of all nylon was staple, as was 90% of the polyester on the market. In fact 28% of all carpet fiber was staple. But as of last year, staple accounts for only 9% of the market—PET staple makes up 8%, polypropylene makes up another 1%, and nylon staple has entirely vanished from the scene.

The most significant development over the last five years has been the huge shift from nylon to polyester in the residential market. Led by the big mills, as well as relative newcomers Phenix/Looptex and Engineered Floors and a whole host of smaller mills, some established and some brand new, polyester has taken massive share from nylon, mostly at the lower end.

The fundamental mechanism for this transition has been technological development, which has enabled the shift from PET staple to filament, and perhaps the biggest driver has been growth in the multi-family market. Firms like Engineered Floors have capitalized on this market, which is price driven and also has a higher turnover rate than residential carpet in single-family homes and condos.

While the growth rate of the multi-family sector is no longer accelerating, industry experts are convinced that the market still has two or three years of significant growth before falling back to more viable long-term levels of activity.

Then there’s solution dyeing, which is currently gaining traction in the residential market, led by solution-dyed PET, though it has traditionally been focused on the commercial market. In the case of commercial carpet tile, it’s all pre-dyed (and the vast majority of pre-dyed yarn is solution dyed), because carpet tiles generally use nonwoven primary backings, which don’t have the structural integrity to survive wet dyeing processes. The only exception is for printed carpet tile, like Milliken’s process, where the dye is applied on finished carpet.

Solution-dyed products offer two key advantages, resistance to staining and to fading. And one possible disadvantage is soiling from processing oil residue. All fiber is coated in oil for the processing stage—twisting, heatsetting, crimping, spinning—and that oil comes off when the carpet is wet dyed, but if it’s solution-dyed, that oil needs to be removed, a process called scouring. Oil residue attracts particles, soiling more easily. The degree to which the manufacturer cleans off that oil plays a big role in determining how well the carpet performs.

In the last couple of years, residential carpet mills have started to appreciate the advantages solution-dyed fiber can bring to the residential customer. The trend toward solution dyeing has been led by polyester firms like Engineered Floors, but many of the mills are now offering solution-dyed products, in both nylon and polyester.

For a few years, Invista has had a solution-dyed Stainmaster nylon for the residential market called SolarMax, marketed for its resistance to fading from sunlight. But after some research and marketing, Invista realized that the fiber, ideally combined with the firm’s cushion backing, was an effective solution for households with pets, thanks to the stain resistance of the solution-dyed fiber. At Surfaces, the product was relaunched as Stainmaster PetProtect.

Another trend is the growth in residential ultra-soft fiber. Toward the end of 2011, the market was flooded with new softer fibers, including Stainmaster TruSoft from Invista and Mohawk’s SmartStrand Silk, an ultra-soft triexta. This trend caught on fast, and now, two years later, so many mills are offering softer fibers that it’s no longer as much of a differentiator, so mills aren’t hyping it as much. At Surfaces two months ago, the mills had plenty of products with ultra-soft fibers, but most were more interested in talking about color, design, weight and price point.

Whether ultra-soft fiber has truly established itself or whether it’s captured a niche and lost its broader momentum will likely become clear over the course of this year. Just about everyone agrees that it’s a clever strategy. For one thing, it’s a counterbalance to the commoditization going on at the lower end, driven by the explosion in polyester (PET) filament, and an attempt to shore up the higher end, where most of the ultra-softs are positioned.

It’s also a trend that makes a lot of sense. After all, as carpet has lost share of the home to hard surface over the last couple of decades, it has been relegated to the more private areas of the home, like the dens and bedrooms, where foot traffic is not as heavy and where coziness and comfort are paramount. And other than the bathroom, it’s where there’s the most barefoot traffic, and where people are most likely to recline on the floor, so a soft carpet can make a tremendous impact in these spaces.

This relates to the other fortuitous aspect of the ultra-soft trend—the selling process. Retailers all around the country report success with variations on the same basic technique, enabling customers to touch it—ideally alongside a carpet sample that isn’t ultra-soft, and maybe one that the customer was, until that moment, intending to purchase.

However, there are challenges. There are reports of homeowners running into issues vacuuming their ultra-soft carpet—there’s no shortage of YouTube videos lamenting this problem. The big mills offer guidance on the issue of maintenance and using the right vacuum, but some consumers are unwilling to invest in machinery just because this carpet needs to be treated differently. Also, because of its construction and the increased surface area of the low DPF fibers, ultra-soft carpet has a tendency to both soil easier and crush down, though these issues can be resolved with the right treatments and styling techniques. While these problems may end up impacting the adoption of ultra-soft carpet, what seems more certain is that carpet fiber has gotten as soft as it can. A four denier per filament (DPF) fiber, which used to be the realm of bath mats, is about as low as the industry can go.

|

U.S. FACE FIBER CONSUMPTION |

||||||

| Polyester fiber (which includes triexta in this chart) continues to take share from the other fiber categories, now accounting for 40% of all U.S. carpet fiber consumption, and if this growth rate continues, in a couple of years polyester could very well be bigger than nylon. PET alone already accounts for 42% of the residential market. | ||||||

|

U.S. Consumption of Carpet & Rug Face Fiber |

||||||

|

Nylon

BCF |

Nylon

ST |

PET/PTT

BCF |

PET

ST |

PP

BCF |

PP

ST |

|

| 2000 |

43%

|

18%

|

1%

|

9%

|

28%

|

1%

|

| 2001 |

43%

|

18%

|

1%

|

10%

|

26%

|

1%

|

| 2002 |

45%

|

18%

|

1%

|

10%

|

25%

|

1%

|

| 2003 |

44%

|

18%

|

2%

|

10%

|

25%

|

1%

|

| 2004 |

46%

|

18%

|

2%

|

10%

|

23%

|

1%

|

| 2005 |

45%

|

15%

|

3%

|

11%

|

24%

|

1%

|

| 2006 |

46%

|

14%

|

5%

|

11%

|

22%

|

1%

|

| 2007 |

46%

|

13%

|

6%

|

12%

|

22%

|

1%

|

| 2008 |

47%

|

9%

|

9%

|

12%

|

21%

|

1%

|

| 2009 |

49%

|

6%

|

13%

|

12%

|

18%

|

2%

|

| 2010 |

53%

|

2%

|

18%

|

8%

|

18%

|

2%

|

| 2011 |

52%

|

1%

|

24%

|

6%

|

15%

|

2%

|

| 2012 |

47%

|

1%

|

29%

|

8%

|

13%

|

2%

|

| 2013 |

46%

|

0%

|

32%

|

8%

|

13%

|

1%

|

Last year, residential carpet business was up by single digits while the commercial market was about flat, and there are signs that the economy isn’t building on momentum, following some strong growth last year. January housing starts showed the biggest drop in nearly three years, falling 16% from December, existing home sales were down 5.1%, and homebuilder sentiment has also plunged. Mind you, so has the temperature, and there’s no real consensus on whether these statistics are even worth examining right now. According to UBS economist Maury Harris, “It may take until the spring to get an accurate assessment of the state of the housing market, given the severe weather conditions across many regions of the country.”

More broadly, gross domestic product went from a 4.1% increase in the third quarter of 2013 to 3.2% in the fourth quarter, hiring has been weak so far this year, and there are concerns that the Federal Reserve is on the verge of reducing its bond-buying stimulus.

Then there’s the petrochemical industry, where the raw materials for most carpet fiber are produced. Since 2005, U.S. oil production has gone up 60% to eight million barrels a day as the result of new technologies—hydraulic fracturing or fracking—that have enabled the extraction of oil and gas previously not accessible. In addition, fracking has led domestic natural gas production to grow so rapidly that it outpaces domestic demand—and last year the U.S. topped Russia as the largest exporter of natural gas in the world. U.S. hydrocarbon production, combined with relatively weak demand both domestically and globally, has been a stabilizing force in the U.S. market, at least for now. Fracking is a lucrative but controversial technique that has been strongly implicated in increasing local seismic activity, and many environmentalists claim that fracking chemicals and natural gas often contaminate groundwater.

Last year was fairly stable in terms of raw materials for the fastest growing fiber category, PET, and all signs point to prices remaining steady or even easing this year. According to PCI Fibres, the only bottleneck has been in capacity for paraxylene, the raw material for PTA, which, along with MEG, is the component chemistry for making PET polyester. However, new paraxylene capacity is coming on board this year, which should further ease pricing.

Currently, it’s cheaper to make PET carpet fiber from recycled plastic bottles than from virgin fiber. Recycled polyester sells for about $0.70 per pound, while virgin PET is more like $0.80 to $0.82 per pound. However, as demand rises for recycled content, and as new paraxylene capacity softens prices, the delta will narrow and could vanish entirely.

It will be interesting to see how mills respond if virgin PET becomes cheaper than recycled PET. Mills get a lot of mileage out of claims of recycled content in their PET carpets. When staple PET fiber was the norm, there was a lot of carpet made out of 100% recycled PET, but it’s been a learning curve with PET filament, and to date recycled content has gone as high as 50%. Will the mills focus as much on the green profile of their PET carpet if it’s cheaper to make carpet out of virgin fiber?

Virgin nylon 6, meanwhile, is more like $1.30 a pound, and that’s a big part of the reason why mills have so enthusiastically embraced polyester fiber. The problem is that the nylon market does not control the prices because its raw materials serve larger markets, while it’s the opposite situation for polyester, whose market dwarfs that of nylon. That can make nylon pricing a lot more volatile. For instance, significant new caprolactam capacity is being added in China, and some U.S. experts believe this could blow a hole in nylon 6 pricing, particularly if the market remains sluggish.

That volatility is reflected in an announcement last month by several leading suppliers of nylon 6 raw materials that they would be increasing prices—in North America, Honeywell and BASF both announced a $0.10 per pound increase for caprolactam and nylon 6 resins—in reaction to a sudden spike in benzene prices toward the end of the year (benzene is the key raw material for nylon production). Since then, benzene prices have started heading back down. That’s a big increase to be passed down the line, and it may face challenges, considering the softness in the market. Nevertheless, there are concerns about benzene capacity in the years to come, with crackers increasingly rely on lighter feedstocks like ethane that yield less benzene byproduct.

Two market leaders in nylon 6,6 production, Invista and Ascend, get to the nylon 6,6 polymer in different ways. Invista uses butadiene while Ascend uses propylene. And while butadiene prices have been fairly low and stable, propylene prices have been up. Last year, Ascend started doing its own propane dehydrogenation from a facility in Texas. The process allows the firm to take advantage of the abundance of propane in all the shale gas being domestically produced, which it turns into propylene.

GREEN UPDATE

It appears as though nylon 6,6 is about to get a lot greener. Nylon 6 has made more progress with post-consumer recycled content than nylon 6,6, but it looks like nylon 6,6 may be on the verge of some bio-based breakthroughs. Industry insiders report that new raw materials from bio-based sources are being developed for the monomer units that are used to make nylon 6,6 polymer, and product should start coming out this year or next, though full commercial production won’t come for a few more years.

If it pans out, there could be nylon 6,6 on the market with a green profile like that of DuPont’s Sorona, which is a triexta polymer with one of its component made from bio-based content (37%). Polymers made this way are fully recyclable and molecularly identical to polymers made entirely of petrochemicals.

When it comes to polyester, most of the big carpet mills offer carpet with 25% to 50% post-consumer content derived from drink bottles. However, the green story is largely on the front end, because on the back end, once the carpet has served its useful life, it is proving to be a headache for recycling. Carpet collectors make the bulk of their money by selling nylon carpet, because recycled nylon has end use markets, like as an engineered resin for parts in the automotive industry. And while polyester bottles have plenty of end use markets (most significantly, carpet), polyester carpet, because of the dyes and treatments on it, is not suitable to be used for either drink bottles or carpets…or much of anything else.

As things stand now, the carpet reclamation industry is drowning in PET carpet. Not only do collectors end up paying to get rid of it, but they also make less money because less of what they collect is nylon. It’s a problem that is anticipated to get worse in the coming years, as today’s volumes of manufactured polyester carpet come to the end of their useful lives. But if something isn’t done—if end use markets aren’t developed—long before then, by the time that carpet is ready to be recycled there won’t be a reclamation industry around to do it.

These days, a lot of sustainability talk is about transparency and green chemistries. Over the years, as the industry has developed, it has abandoned dubious or downright hazardous chemistries and attempted to develop more responsible products that still do the job. Oftentimes, the replacement materials come from the same chemical family because of unique performance characteristics based on their molecular structures.

One such example is soil repellent technology. In 2000, market leader 3M decided to change the chemistry of Scotchgard to eliminate PFOA and PFOS related chemistries, which had been shown to be bioaccumulative and, at high exposure levels, toxic. Instead, the firm turned to fluorotelomers with shorter chain lengths, which are persistent but not bioaccumulative, and do not share the same toxic profile as PFOA.

Nevertheless, halogenated materials (which includes chemistries using chlorine, bromine and fluorine) remain in the crosshairs of scientific and medical researchers, as well as environmentalists.

One firm that believes it has come up with an alternative is ArrowStar LLC, whose ArroShield Evo claims the same performance in a randomized polymer that is halogen free. The product, a polyurethane with silicone polyol units, can be applied as spray, foam or exhaust, and it gives off extremely low VOCs and has a very low toxicity, according to the firm. Also, it costs about the same as soil treatments already on the market.

ArrowStar has four patents pending on its chemistry, and it is currently working with several mills with ArroShield Evo. If all goes well, mills will start coming out with product using this treatment in the near future.

The firm has a pilot plant in Dalton, which will reach full production in a couple of months. Next, the firm is targeting the hard surface market. It is already testing its product with grout sealers as well as concrete sealant. And it will also be targeting the textile market.

|

FIBER PERFORMANCE |

|

There are clear chemical differences between the synthetic fibers in the carpet market—polypropylene, polyester, triexta, nylon 6 and nylon 6,6. For instance, polypropylene has the lowest melting point, followed by nylon 6, triexta, PET and nylon 6,6. There are also unique performance characteristics. The nylons are more resilient than polyester and even more resilient than polypropylene. Polyester and triexta have a natural stain resistance that nylon does not have, but they’re also oleophilic (affinity for oil), though not as much as polypropylene. Nylons are not as oleophilic. Also, because of nylon 6,6’s chemical structure, its dyeing can be more involved than nylon 6, but nylon 6,6 has better washfastness, though the two are more equivalent when solution-dyed. |

PRODUCER HIGHLIGHTS

The leading independent fiber producer is Invista, whose premium residential offering, Stainmaster, has long been the most visible brand in the flooring industry. On the commercial side, the firm’s Antron brand offers a range of fiber constructions. All of Invista’s fiber is made of nylon 6,6, with the exception of its Stainmaster Essentials brand, a value priced offering that includes both nylon and polyester—Pharr Yarns is among the firms that make the polyester for Stainmaster according to Invista’s exacting specifications—with the firm’s soil and stain resistance technologies. Stainmaster Essentials is sold through Stainmaster Flooring Centers and at Lowe’s.

Two years ago, the firm came out with Stainmaster TruSoft, the lowest denier per filament nylon fiber on the market, and it has continued to refine that technology. At Surfaces earlier this year, Invista unveiled PetProtect, a solution-dyed nylon 6,6 residential fiber system. According to the firm, the fiber offers enhanced soil and stain resist technology, and it also has a tendency to repel pet fur, a result of its processing technique.

Invista recommends using its Stainmaster carpet cushion with PetProtect. The carpet cushion features a breathable moisture barrier on the top of the pad, so it will stop liquids (and odors) from penetrating the cushion and subfloor, while allowing moisture rising from below to dissipate. At the show, Dixie Home, Phenix and Royalty came out with PetProtect carpets.

While Invista is a nylon 6,6 specialist, Aquafil, which is headquartered in Italy, is focused on nylon 6, except for some non-carpet nylon 6,6 filament it makes in Europe.

Last year, Aquafil acquired a German operation called Xentrys from Belgium’s Domo Group. Xentrys has a capacity of about 40 million pounds a year of filament yarn manufacturing and about the same twisting and heatsetting capacity, and Aquafil is using it to produce commodity white yarn. In exchange for Xentrys, which Aquafil has renamed Aqualeuna, Aquafil turned over its engineered plastics business to Domo, so Aquafil is now a textile specialist—80% of its business is carpet yarn and 20% is textile yarn.

Last year, Aquafil USA recorded 20% growth, driven by demand for its Econyl product, which is made of 100% recycled content, as well as success in its hospitality business. The firm has 14 facilities across the globe, including its existing facility in Cartersville, Georgia as well as a second Cartersville facility that will open in June. The firm also has multiple facilities in Europe and Asia.

Universal Fibers produces a broader range of fiber than Invista or Aquafil. It makes, in order of volume, nylon 6,6, nylon 6, polyester and now triexta. Last year, the firm entered into a licensing agreement with DuPont to produce carpet from its Sorona triexta polymer. It’s a global agreement for residential, commercial and automotive carpet, with a couple of exclusions: the North American residential market, where Mohawk has exclusive rights; and the residential market in Australia and New Zealand, where DuPont has an agreement with Godfrey Hirst.

Universal is interested in using triexta in its substantial automotive business, and it’s also focusing on the commercial market in Asia, along with European markets. The firm is currently trialing its fiber, which it calls “Rise featuring Sorona by DuPont,” in European and Asian mills. In terms of the North American commercial market, Universal is still in the early development stage.

The firm is solution dyeing its triexta offering, using its Universal color technology, and it will be extruding product at its facility in Bristol, Virginia and in its facility near Shanghai, China.

Also, this year Universal is launching solution-dyed Trestiva, which is a nylon 6 version of the 600 denier building blocks it currently offers in nylon 6,6. The offering hits lower price points, and it should help the firm build its business not just in the domestic market, but in Asia as well. Trestiva comes in 70 colors. Last year, Universal’s global business was up by double digits.

Ascend, which was Solutia until its acquisition nearly five years ago by SK Financial, makes nylon 6,6 BCF fiber, though that only accounts for a modest portion of its business, most of which is involved in non-fiber plastics. It also has a chemicals division. Ascend’s vertically integrated U.S. carpet business is two thirds commercial and one third residential, and last year that business was up by low single digits.

About a year ago, Ascend introduced a product called Ombre, which uses a mechanical process to randomly impart differing levels of dye affinity along its length, essentially creating a look ordinarily achieved through space dyeing. Ombre goes mostly to the commercial market, but Ascend has also come out with Ombre Soft, which targets the residential market and is already being used by some carpet mills.

Pharr Yarns makes carpet fiber not just for mills but also for other fiber producers, generally in the form of specialized products like Stainmaster’s PET. While it makes product in small lots for many mills, the biggest chunk of its product goes to Phenix. Most of Pharr’s facilities are in the Carolinas, totaling around a million square feet of manufacturing footprint.

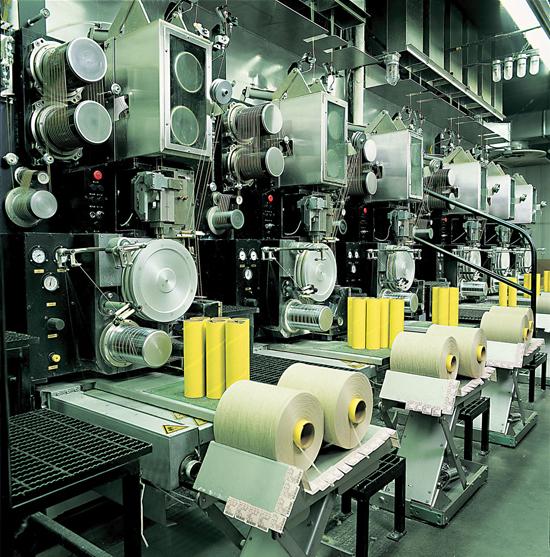

Over the last year, Pharr has made significant investments in capacity, expanding twisting and heatsetting, as well as extrusion, which has been boosted about 20%. The firm reports that a lot of its twisting capacity is being used on polyester, which requires more twisting to boost its resilience. Because both low denier yarns and polyester require extra twisting, slowing production, the end result is that twisting capacity in the industry is going down, and more mills than ever are coming to Pharr for that extra capacity.

Like Universal, Pharr has a licensing agreement with DuPont for its Sorona, which it uses for Mohawk’s commercial demand, creating specialized products like fleck yarns.

Zeftron, which specializes in solution-dyed nylon 6 for the commercial market, is a division of Shaw Industries that sells its fiber to the open market. Zeftron was originally a Honeywell brand, and when Shaw purchased Honeywell nine years ago it used its residential yarn internally but maintained Honeywell’s commercial fiber business.

Zeftron is enhancing its solution-dyed offering with about a dozen new colors, including six or seven vivid hues (like vivid yellow, hot pink and bright purple), some neutrals and a metallic, taking its total offering up to about 120 colors. Some of the more saturated colors are targeting the hospitality market.

Copyright 2014 Floor Focus

Related Topics:Engineered Floors, LLC, Mohawk Industries, The Dixie Group, Shaw Industries Group, Inc.