Masland Celebrates 150 Years - Apr 2016

By Calista Sprague

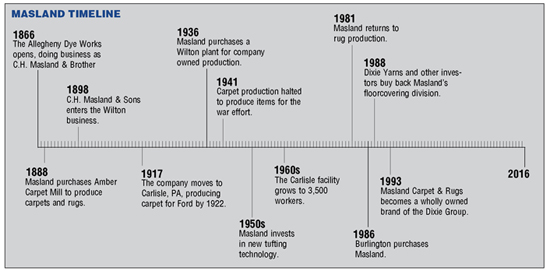

Few manufacturers survive to celebrate their centennial anniversary, fewer still reach their sesquicentennial, but this year Masland will celebrate 150 years of continuous business. To navigate world wars, economic recessions and depressions, industry shifts and fluctuating consumer preferences, Masland has relied on a legacy of integrity, innovation and calculated entrepreneurial risk.z

Today Masland Carpet and Rugs is one of five brands manufacturing higher end products for the Dixie Group, but for the majority of its lengthy history, it was a family business. Founder Charles Henry Masland hailed from a family of hosiery weavers in England. When mass production began to replace the cottage industry that sustained his parents and siblings, young Charles set sail for opportunities in North America, serving for several years in the armed forces, first for England in Canada and then for the United States.

After fighting for the Union during the Civil War, he took a job dying yarn. Charles possessed an entrepreneurial spirit, and just two years later, in 1866, he combined resources with his brother James and friend Joseph Scargle to purchase the dye business and convert an abandoned vinegar plant into a yarn dye house in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Scargle withdrew from the enterprise early on, and the company became known as C.H. Masland & Brother.

Although it was common practice among competitors to return less yarn to customers based on the heavier weight once dyed, the Masland brothers conscientiously returned every ounce of yarn they received, and soon built a strong reputation for integrity.

In 1875, Charles bought his brother out of the business, which then became C.H. Masland. After another decade of success in the dye business, Charles was ready to launch into his next challenge, shifting to carpet and rug production. He sold the dye works and purchased Amber Carpet Mills in Kensington, Pennsylvania. New buildings were erected and 30 ingrain looms began turning out product.

By this point Charles wanted to retire. In 1888, he formed a partnership with two of his six sons. Frank Elmer Masland, known as F.E., and his brother Maurice Henry Masland, known as M.H., ran C.H. Masland & Sons, but Charles retained title to the real estate and the sons rented from him.

Consumer tastes were changing, so in 1898 Masland purchased tapestry and velvet looms to manufacture Wilton and Brussels carpets. Just ten months later, the new equipment burned in a fire at the mill, a huge loss for the company. Masland leased a Wilton mill in order to offer the popular new styles of carpets, but would not return to in-house Wilton production for nearly four decades.

At several points in Masland’s history, short-term sacrifices were made to ensure long-term success of the company. In 1907, for example, Masland’s officers made the difficult decision to draw no salary for a year, a stop-gap measure that kept the mill operating during a national financial crisis and economic recession.

Once the crisis passed, Masland’s leadership set about growing the business for several years, but during WWI, carpet weaving came to a halt. In order to support the war effort, looms were converted to produce heavy, white canvas duck, which was then dyed and flame proofed for use as tenting material. Many of the old ingrain looms produced blankets for soldiers as well.

Masland was poised to expand at the end of the war, and in 1919 purchased land for a new facility on former fairgrounds in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The expansion allowed the company to manufacture woven carpet for the Ford Motor Company in 1922 and eventually for much of the U.S. auto industry.

Masland was known for innovation early on, introducing the first manufactured carpet fiber before WWI and installing its first 9-foot velvet power broadloom in 1917. In the early 1920s, in addition to innovations in the auto industry, the company garnered national attention for its Argonne rugs, developing what became known as the “Masland Method” of printing colorful patterns on woven rugs.

Although they had no way of knowing it in the roaring ’20s, the decision to diversify into the automotive market would eventually save Masland from ruin, providing an additional revenue stream to help weather the Great Depression.

At the lowest point in the depression, even the auto industry’s contract terms left little margin for profit, and once again short-term sacrifices were made for long-term gain. This time, Masland associates agreed to a reduction of wages to ensure income for the coming months, another example of the cooperative spirit between management and associates that helped keep the company solvent during lean times.

The Great Depression had not yet ended, but in 1936 Masland took a calculated risk that would later prove vital, investing in Wilton production through the purchase of the Barrymore Seamless Wilton brand. In retrospect, the acquisition strengthened the company, which otherwise could not have competed in a market shifting away from woven goods.

In 1939, Masland began a pilot program to again convert looms for the production of cotton duck. Two years later, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Masland converted fully to war production, temporarily becoming the largest producer of canvas duck in the world. The company also manufactured parachutes as well as clothing for the Navy, which became a Sportswear Division after the war. For its efforts, Masland was the first in the textile industry to be awarded the Army-Navy “E” award for excellence, which it accepted a total of five times.

Following WWII, the fourth generation of Maslands took the helm. Frank E. Masland III, known as Mike after an uncle joked that there were too many Franks in the family, attended Princeton’s ROTC program and fought valiantly in the war, earning a Bronze Star. When he returned home, he assumed leadership of Masland & Sons, a position he held for several decades. Among his many accomplishments, Mike is credited with transforming the organization from a predominantly family held company to a publicly held, multi-national corporation.

In the early 1950s, the advent of the tufting machine allowed carpet makers to increase production. The average price of carpet dropped, making it affordable for a wider segment of the population, and wall to wall carpeting came into vogue. Masland took a risk to invest early on, improving both quality and productivity in the process.

Masland continued to innovate in the automotive industry as well, creating a non-woven needlepunch carpet for cars, trucks and airplane interiors that became one of the company’s best sellers. Later, the Masland automotive division helped develop the first molded carpets used in vehicles today.

By the 1960s, carpet had become America’s favored floorcovering, and both Masland’s floorcovering and automotive divisions flourished. It had become the largest employer in town, growing from 900 to 3,500 workers at the Carlisle facility’s peak, and practically everyone in Carlisle had a connection to Masland.

The company’s sustained growth soon spurred the need for expansion. In 1965, Masland & Sons’ stock went public to raise capital, and in 1968, the burgeoning floorcovering division moved to a larger facility in Atmore, Alabama, leaving the automotive division in Carlisle, in close proximity to the automotive industry.

Masland reinvented its image in the early 1980s, developing a new marketing strategy with plans to become a leader of style and fashion. More sophisticated colors and textures were introduced in the product lines as well, to appeal to the residential design trade. Masland also introduced a line of area rugs, which it had stopped producing mid century. Eight designs quickly multiplied, and the company expanded the category to meet demand from designers for custom rugs.

Finally, in 1986—after 120 years—the Masland family gave up control of the business, selling Masland & Sons to Burlington Industries. But only two years later, a group of investors from the Masland family, Dixie Yarns and Prudential Insurance bought back the floorcovering division. And in 1993, Masland became a wholly owned brand of the Dixie Group, as it remains today.

The Masland brand still thrives, operating its own headquarters in Mobile, Alabama. More than 700 Dixie Group associates support the Masland brand, producing millions of square yards of carpet each year in Alabama and Georgia.

To kick off Masland’s sesquicentennial, all 50 Masland residential salespeople joined the management team for a celebration during the national sales meeting in Mobile this past January. The salespeople accounted for more than 750 years of combined service for Masland, including individuals with two days of service up to 53 years. In addition, the anniversary will be marked with commemorative coins presented to selected dealers, and an anniversary promotion to run with selected dealers through the end of the year.

The founding family may no longer run Masland, but C.H. Masland’s legacy of integrity and innovation persists 150 years later, and its associates still endeavor “to deliver the highest quality and provide the best service in the floorcovering industry.”

Copyright 2016 Floor Focus

Related Topics:Masland Carpets & Rugs, The Dixie Group